|

| |

|

|

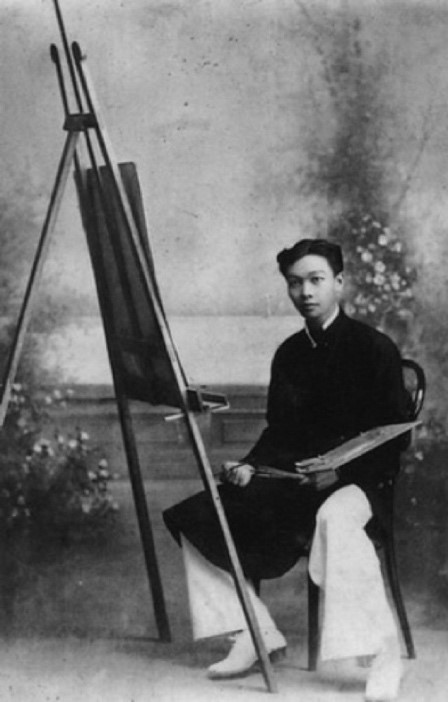

Figure 5, Left: Photograph of Victor Tardieu (1870-1937) in Hanoi, late 1920s. Photographer unknown / Public domain. Figure 6. Right: Photograph of Nam Sơn (Nguyễn Vạn Thọ, 1890–1973) in 1919, courtesy of the artist’s family archives. |

|

|

|

While painting at the University, Tardieu was befriended by Paul Monet, a former geographer with the French army. An advocate of Franco-indigenous relations and a critic of colonial exploitation,15 Monet founded the Hanoi Annamite Students Centre [Foyer des Etudiantes Annamités] in 1922.16 Meeting Tardieu at the university, Monet introduced him to a talented Vietnamese artist Nam Sơn (Nguyễn Vạn Thọ, 1890–1973) and urged him to develop his potential as a painter. What developed was a striking relationship between mentor-student, artist-friend, and perhaps father-son, which had profound meaning for both men and major consequences for modern Vietnamese painting.

The story of Victor Tardieu and Nam Sơn (see Figure 5 and Figure 6) and the other personalities in their orbit cannot be separated from the history of the visual culture of Vietnam and reminds us that history is often made, even changed, by individuals. The foundation of the EBAI owes as much to their partnership as it does to the social and political climate of the times.

The foundation of a fine arts school in Indochina

It was Nam Sơn who proposed the idea of a vocational art school for indigenous students. A long-held dream, he had already written a proposal for the establishment of an art academy that would deliver a western inspired Beaux-arts curriculum to indigenous students in Hanoi. He urged the well-connected Tardieu to lobby the 23rd Governor-General of Indochina, Martial Merlin (1860–1935) for its creation. With what seems astonishing alacrity, the colonial administration agreed, and the EBAI was created by decree in October 1924. That Merlin had only just survived an anti-colonial assassination attempt in June may have had something to do with it. Duiker asserts that the attempt sent “shockwaves throughout the French community in Indochina.”17

Government sponsorship of such a prestigious cross-cultural project would be a powerful tool in countering criticism of its slowness to implement the benefits of the mission civilisatrice. Here was an opportunity to instil the aesthetics, history and ascendancy of French civilization in all its visual brilliance. Within the year, the colonial academy, dedicated to Western classical art instruction, opened its doors, with Victor Tardieu confirmed as principal and Nam Sơn as deputy, and both as co-founders. The optics could not be bettered (see Figure 7).

|

| |

|

Figure 7 Photograph of Victor Tardieu, front centre, and Nam Sơn, front right, with teachers and students of the EBAI, Hanoi, c. 1930, courtesy of Nguyễn Văn Ninh private collection.18 |

|

|

|

During its 20 years of operation, the EBAI introduced to Vietnam the classical academy skills of anatomical drawing and oil painting.19 The colonial academy produced 128 highly trained graduates, many becoming renowned international artworld names, including Nguyễn Phan Chan (1892–1984), Tô Ngọc Vân (1906–1954), Lê Phổ (1907–2001), Nguyễn Phan Chan (1892–1984), Vũ Cao Đàm (1908–2000) and Nguyễn Gia Trí (1909–1993). The EBAI followed a classical western art curriculum with classes in drawing, painting, composition, and perspective, as well as anatomy and art history, based on the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, but adapted to an indigenous scenario in Indochina.20

After the announcement of the creation of the school, Tardieu and Nam Sơn went to France to recruit teachers for the new academy and spruik the new and enhanced conditions of the Prix de l’Indochine.21 As part of Tardieu’s lobby to the colonial administration, the art prize was now tied to the EBAI, and its stipend increased from six-months to a two-year residency, including a year of paid teaching at the school, ranking it synonymous with the Prix Nationale and an extremely desirable award in a France still recovering from the economic and psychological trauma of the Great War (1914–1918).22

In all, over 60 French artists taught at the academy, including leading lights of Parisian modernist movements between the world wars. Far from being considered a colonial backwater, the EBAI attracted highly skilled artist-teachers from the ateliers of Paris. Moreover, many faculty members, including Victor Tardieu, Alix Aymé (1894–1889), Joseph Inguimberty (1896–1971) and Andre Maire (1898–1984), dedicated their lives to teaching at the academy, to their students, and to living in Asia.

A classical curriculum

By instruction and example, Tardieu introduced to Vietnam, the concept of the vocational artist with a reproducible pedagogical method. His aim was to train artisans to be artists.23 Though Vietnam had a long artisan history, the concept of ‘artist’ was an entirely new idea and, along with oil painting, represents a significant innovation, requiring a new position of họa sĩ [artist], in addition to the existing thơ vẽ [artisan] in Vietnamese society, which traditionally had made no distinction between art and artisanry.24

Faculty was made up of French teachers who were also artists in their own right, who produced and taught their art and craft. The curriculum included a mix of art history, practice, theory, along with the passionate ideas and philosophies of romanticism, idealism, and poeticism. Western art concepts, such as subjectivity, objectivity, perspective, individualism, and authorship (such as signature or stamp; in some cases, both) were introduced to students. Western art practices such as oil painting, pigment mixing, life drawing (with models sourced from the local prison), and outdoor painting [en plein air] became the fulcrum of the academy’s rigorous tuition (see Figure 8).

|

| |

|

Figure 8 Photograph of a life-drawing class at the EBAI, c. 1925, courtesy of Fine Arts Publishers, Hanoi.

|

|

|

|

Perfected by the impressionist and post-impressionist art movements, en plein air was designed to render a painting in the moment rather than from recollection back in the studio. Being in the open air and at the mercy of the elements necessitated excellent and fast drawing skills as well as portability of equipment and materials, such as easels and satchels, which were relatively recent inventions.

These stylistic and technical interchanges were put to additional uses by war era artists at the battle and home fronts, or guerrilla-style raids, all of which required a fast and impressionable drawing method. The ability to draw fast, along with portable equipment (see Figure 9), was not just a requirement but a necessity, as artist Trịnh Kim Vinh (1932– ) recalled, “If the enemy plane arrives while you were drawing, you had to run.”25 Even the technique of pigment mixing was taken out of the studio and used in the field. Artist Phạm Thanh Tâm (1934– ) recounts dangerous missions behind enemy lines to paint posters such as Persistent resistance guarantees victory, Soldiers and people unite, and Destroy French invaders, on village walls in enemy territory during the First Indochina War, “I went by myself, without even a backpack, only a sack containing a bit of gouache, mostly colour pigments, brushes and a bit of binding agents to mix the colours.”26

|

| |

|

Figure 9 A war artist’s kit, including easel, brushes, tube, and satchel inscribed “Cặp vẽ Nguyễn Hoàng - Vượt Trường Sơn,” c. 1972, Central Highlands, HCMC Museum of Fine Arts, photograph by author.27

|

|

|

|

En plein air also created an emotional bond between artist and landscape. In DRV visual propaganda, the Vietnamese landscape from delta to mountain becomes a patriotic motif, legitimising, as Taylor observes, the Vietnamese “claim to their homeland visually.”28 Nguyễn Sáng (1923–1988) and other war artists, such as Phan Kế An (1923–2018) often included soldiers in the landscape, which served multiple propagandistic functions, instilling a love of country, a desire to serve, and a wish to support those who were protecting the nation from being taken away from Vietnamese people (see Figure 11). As painter Nguyễn Sáng articulated, “There is art in the country, the loss of country, [and] the loss of freedom is the loss of everything.”29

The academy is also credited with the revivification of indigenous art forms, such as painting on silk, and, in the case of lacquerware as a painting medium, the innovation of new art form.30 EBAI graduates such as Nguyễn Gia Trí (1909–1993) and Nguyễn Khang (1912–1989) excelled in the fastidious and painstaking technique of working with lacquer, which could express satirical humour (see Figure 10) or convey intense emotion (see Figure 11).

The EBAI also revitalised traditional art techniques, such as woodblock printing, silk painting and lacquerware. Supply shortages in the colony of paper, oil paints, and other materials may have been the catalyst for experimenting with watercolours on silk and woodblock lithographic work. Traditional woodblock printing was a viable and portable alternative in times of shortage, and when supplies ran short during the conflict era, many posters were produced in this medium.31

Many of the aesthetics, techniques and modalities of the EBAI became characteristic of Vietnamese modernism, reproduced in the curriculum of the DRV’s wartime art school known as the ‘Resistance Class’ [Khóa Kháng Chiến], and expressed to a broader and larger audience in the propaganda posters of the revolutionary period.

Poster making at the academy

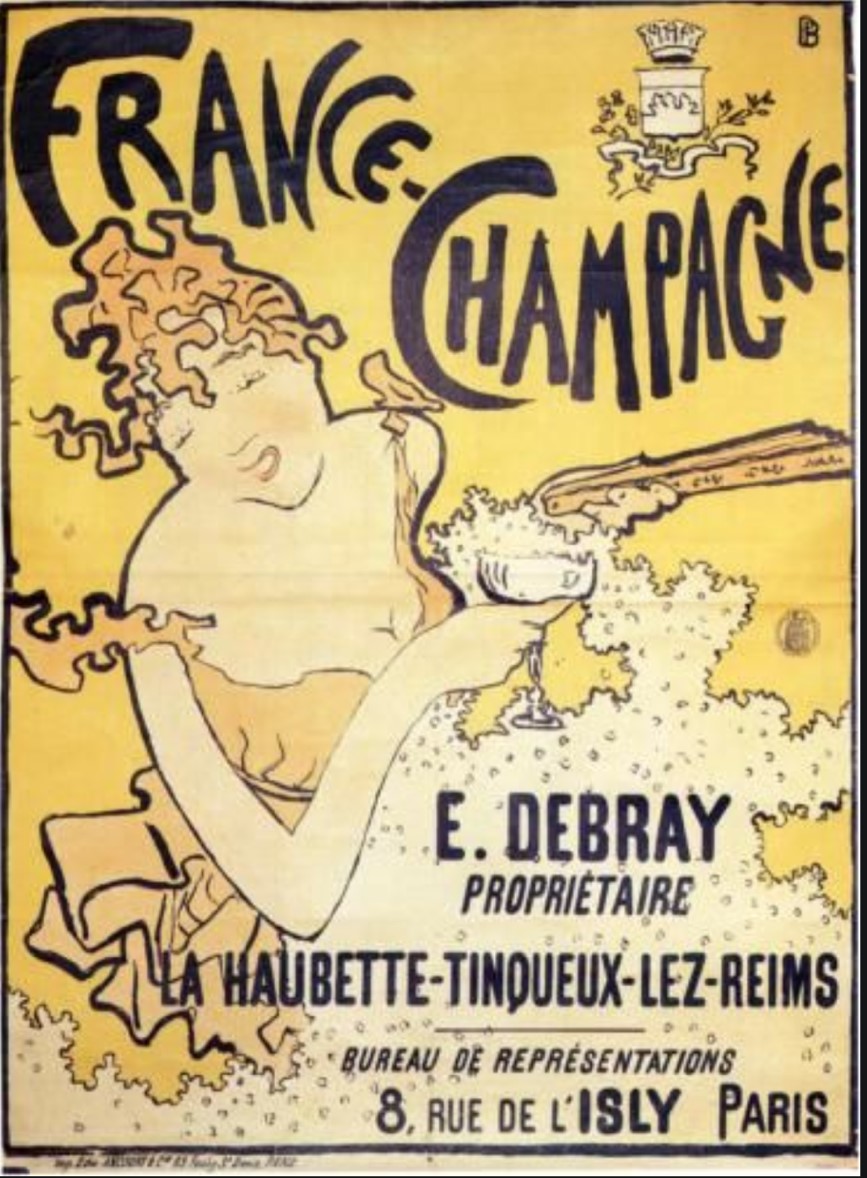

In the nineteenth century, French artists propelled technological and aesthetic innovations in poster making, and the involvement of leading artists elevated the standing of poster-making to high art. In the 1860s, French artist, Jules Cherét (1836–1932) began perfecting the technique of colour printing, known as chromolithography, which made the mass production of posters viable. The budding advertising industry utilised posters to promote events and products from bicycles to ballet. By the 1890s, the revenue-making opportunities attracted aspiring and renowned artists, including Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Édouard Vuillard(1868–1940) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), whose effervescent and imaginative posters caused a sensation in Paris and across the continent (see Figure 12).32 The French term affichiste [poster artist] was coined to designate the new vocational role of the artist-designer of images for posters and other visual materials.

|

| |

|

Figure 12 Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), France-Champagne, 1891, Lithograph, courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington.

|

|

|

|

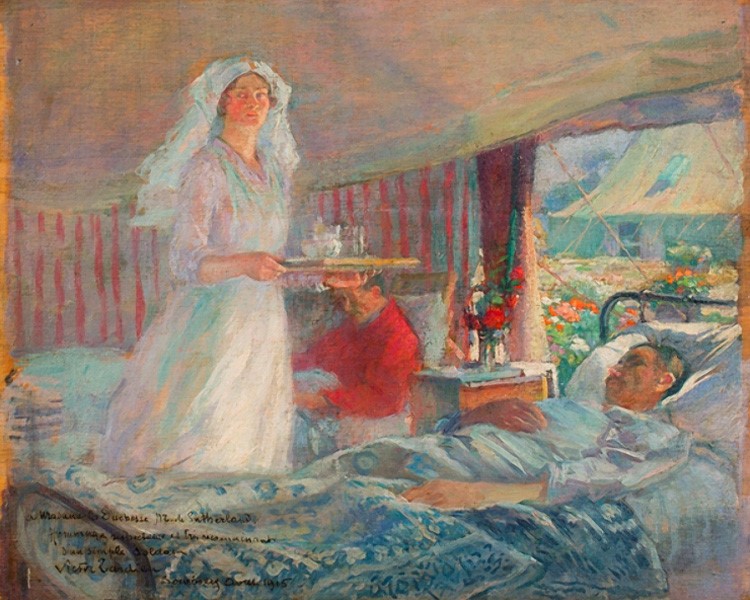

As Europe prepared for war in 1914, combatant nations took advantage of the technology and commissioned artists to advance the national mission through posters designed to mobilise the home front. Tardieu was one of those artists, producing posters and combat art during his war service (see Figure 13). At the EBAI, it is likely he would have endorsed poster-making as a professional vocational opportunity and as a legitimate artistic pursuit. An artist of his lineage and reputation, as well his involvement and that of members of his faculty would have also endorsed poster-making as a fine art, suitable for high aesthetic endeavour as much as the money-making opportunities it offered.

Tardieu also understood the power of the visual in the selling of ideas in commercial and political spheres. He had used these notions when he lobbied for the creation of the academy and the renovation of the Prix de l’Indochine as a promotional tool. A major art prize brought prestige to the colony and the artist themselves, who would in turn produce artworks that would speak to the beauty and tranquillity of the colony and the beneficent colonial mission.

|

| |

|

Figure 13 Victor Tardieu (1870–1937), Hospital in the Oatfield, 1915, Oil on canvas, courtesy of the Florence Nightingale Museum, London.

|

|

|

|

The rapid development of print infrastructure in urban Indochina in the 1920s had dramatically increased opportunities for trained local poster designers, or affichistes, to produce posters for commercial purposes, such as the nascent tourist industry.33 At the academy, students were involved in the preparation of fortnightly magazines involving cartoon illustration.34

Several artists associated with the EBAI became successful affichistes during the colonial era. Hồ Văn Lai, EBAI graduate (1926–1931) produced For your next pleasure trip choose this time . . . French Indochina for the Saigon Tourist Bureau in 1938. His signature and stamp are visible in the right-hand bottom corner (see Figure 14).35 Figures representing ethnic minorities are grouped around the French flag, a propagandistic device extensively used in the Vietnamese visual communication for very different reasons.

|

| |

|

Figure 14 Hồ Văn Lai (c. 1907 – unknown), For your next pleasure trip choose this time . . . French Indochina, 1938, Lithograph, 64 x 84 cm, courtesy of The Ross Art Group.

|

|

|

|

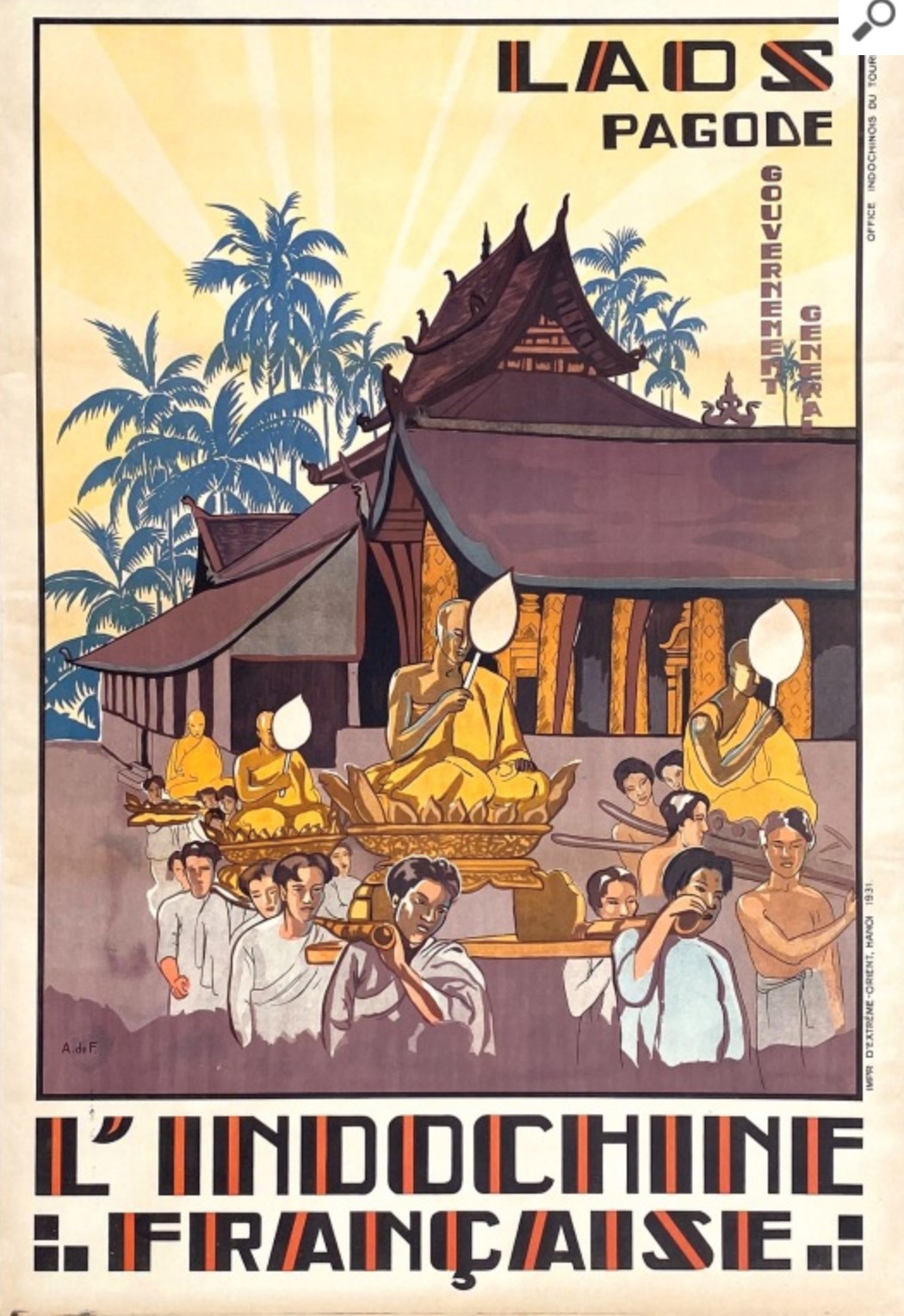

EBAI teacher (1934–1939) Alix Aymé (1984–1989), a renowned female painter in Asia, who had provided poster art previously to the colonial authorities, also contributed an image (see Figure 15), signed ‘A de F’ for Alix de Fautereau (her first husband’s name) to the exposition. She remarried in 1931 to Colonel later General George Aymé of the French Army in Indochina. Jos-Henri Ponchin (1897–1981), the son of one of the faculty teachers and 1922 Prix de l’Indochine winner, Antoine Ponchin (1872–c. 1932), was commissioned to paint a series of images of French Indochina to promote the 1931 International Colonial Exposition in Paris (see Figure 16 and Figure 17).

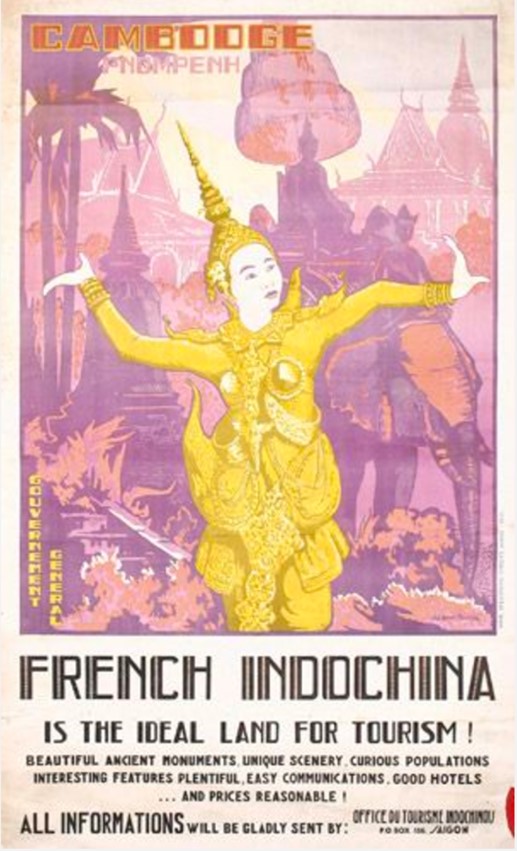

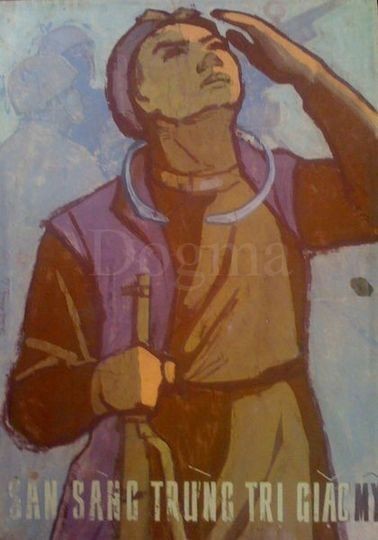

Ponchin’s distinctive imagery catches the orientalist interpretation of the exotic Far East. There are also striking stylistic parallels in the style of Ponchin’s posters and that of some of the wartime posters produced for the DRV, as demonstrated in the colour palette of the poster Ready to chastise the American invaders (see Figure 18). These posters share a similar pastel palette and figurative line, which are also evident in Trần Văn Cẩn’s 1960 composition, Coastal Militia Woman, considered to be an exemplar of nationalist art (see Figure 19).36

|

| |

|

Figure 15 Alix de Fautereau / Aymé (1884–1989) L’Indochine Francaise Laos Pagode, 1931, Lithograph, courtesy of Saigoneer. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Figure 16 Jos-Henri Ponchin (1897–1981), French Indochina is the ideal land for tourism, 1931, Lithograph, 112 x 75 cm, courtesy of Saigoneer. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Figure 17 Jos-Henri Ponchin (1897–1981), French Indochina, 1931, Lithograph, 112 x 75 cm, courtesy of LiveAuctioneers. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Figure 18 Artist unknown, Ready to chastise the American invaders, Gouache, c. post 1965, courtesy of the Dogma Collection. |

|

|

|

From craft to modernity: Tardieu’s legacy

Tardieu was a significant force for transference of knowledge and skills in a colonial society that largely paid lip service to the education of the colonised. According to Taylor, Tardieu was widely considered to have been “genuinely interested in local art-making technique” and acknowledged the value of indigenous skills and aesthetics.37 Under Victor Tardieu’s tutelage, his Indochinese students became artists capable of producing “what he considered to be genuine works of art.”38 Tardieu encouraged students to take pride in and ownership of their work by signing artworks as individuals. They were no longer anonymous artisans. To the French colons [settlers] of Indochina, Tardieu’s views verged on the radical.

Tardieu’s vision may not have been quite the type of mission civilisatrice many economic-minded colons believed in, but it found fertile ground with other faculty members. Key staff, such as Joseph Inguimberty (Prix Nationale 1924) and Alix Aymé were receptive to and actively engaged with local art and craft traditions, countering anti-colonial critiques of the oppression of indigenous sensibilities. Tardieu’s insistence on taking ownership of artworks (and posters) via signature or stamp continued into the revolutionary period. According to Richard di San Marzano, curator of the Dogma Collection, approximately 80 percent of DRV posters are signed and dated by artists.39 It is not a practice widely seen in other iterations of communist propaganda.

Following Tardieu’s death in 1937, Évariste Jonchère (1892–1956), awarded the 1932 Prix de l’Indochine, was appointed the director of the school until it was closed by the Japanese when they ended French rule by coup d’état in 1945. According to Taylor, Jonchère did not share Tardieu’s enthusiasm for Vietnamese artistry, claiming that “I have seen the artists in Hanoi and they are artisans, not artists.”40 According to Nguyễn Phan, Nam Sơn and other faculty teachers worked around Jonchère’s attitude and continued with the fine arts mission that Tardieu had established, producing some of Vietnam’s most acclaimed artists, including Diệp Minh Châu (1919–2002), Phan Kế An (1923–2018), Bùi Xuân Phái (1920–1988), and Nguyễn Sáng (1923–1988)41.

Through the EBAI and the other art schools, Western skills were handed down through successive generations of Vietnamese artists, who became teachers in these colleges. The celerity of classical techniques such as drawing and gouache, as well as pigment mixing, would prove to be a formidable skill acquisition for artists on the front line or in missions of subterfuge behind enemy lines or during bombardment or in battle. The ability to carry out clandestine mobile acts at speed to avoid capture (reminiscent of contemporary urban graffiti ‘vandalism’) was another ironic consequence of formal French Academy tuition.

Many former students of the EBAI joined the resistance movement setting aside their artistic individualism to pursue the collective independence mission. Nevertheless, their individualism seeps through their work and into the images produced for or directly onto the posters. The subject in the graduates’ artworks migrated from idyllic domestic scenes of girls with lilies and lotuses preoccupied with washing their hair to outdoor scenes in the mountains or by the sea, transformed into warriors with M-16s and AK-47s, and promoted as defenders of the nation (see Figure 19).

In terms of ingrained arts practice, personal loyalties, and a sense of lineage, it would have been virtually impossible to remove the guiding principles and techniques handed down by the French teachers. In turn, the EBAI graduates passed on these principles and techniques to subsequent generations involved in propaganda and art production. Both the French colonialists and the Vietnamese revolutionaries recruited artists to their respective missions and manipulated aesthetics to serve ideological ends. How Vietnamese artists responded to those pressures is a window into the role of creative artists in shaping society and vice versa.

The EBAI is the crucible where Vietnamese tradition and Western modernism was forged, tested, reproduced, reinvented and localised. The EBAI and similar art schools created a forum for the exchange of ideas that were transformative for the students. Faculties included French (and later Vietnamese) teachers whose liberal outlook confronted the prevailing social order and challenged the norms and mores of conservative colonial society. The EBAI was a vortex of modern, exciting, and confronting artistic and social ideas and behaviours.

The fusion of modern Western ideas and Vietnamese traditions was a ‘turning point’ in modern Vietnamese art history, allowing “artists to express themselves within a unique national character and with individual artistic voices.”42 Vietnamese art historian, Nguyễn Quang Phòng argues that European art traditions provided “all the possibilities to express with faithfulness and subtlety the feelings and soul of Asian Vietnamese painters.”43 As paradoxical as it is, Vietnamese artists, expertly and broadly trained in Western visual aesthetics, design, and production, and driven by notions of artistic individualism, were involved in the collective independence project of state-sponsored messages that produced an oeuvre of visual hybrid vigour. Rather than diluting the political message, hybrid vigour enhanced it. Through the agency of artists, Vietnamese propaganda designed to articulate state-sanctioned messages rose above party rote to address a deep cultural need, and, express a collective desire.

The legacy of the EBAI is equivocal because the academy curriculum and creative environment equipped artists with European classical aesthetics and techniques, as well as an expressive and emotional sensibility, which were adapted to the Vietnamese revolutionary mission to instil nationalism in the indigenous population, their fellow Vietnamese. The EBAI is a complicated legacy of the French civilising mission and one that the Vietnamese revolutionary project selectively, perhaps adroitly, sidestepped. Ultimately, for all its ambiguity and ambivalence, the self-serving ideology of mission civilisatrice, which sponsored the fine arts in Indochina through the EBAI, produced a cohort of expert and lyrical artists that were among the most potent weapons used by Vietnamese revolutionaries to bring down the colonial regime, and to confront another, even more formidable world power.

John Michael Swinbank holds a Master of Communication Management and a Master of Visual Communication and Cultural Studies (Research) from Murdoch University, where he is undertaking his PhD studies at the Asia Research Centre. His supervisors are Dr Kathryn Trees, Professor Terence Lee, and Dr Arjun Subrahmanyan. John Michael’s research interests are Visual Communication, Crisis Management, Propaganda, Cultural Studies, Art History, Colonial Studies, and Vietnamese History.

|

|

|

Notes

1

|

|

|

Notes

1In 2016, Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc gifted French President François Hollande a lacquer artwork featuring Tardieu and Yersin, commemorating the expertise they had shared with their adopted country of Vietnam. http://hanoia.com/blog/news/show/the-delicacy-of-vietnam-pms-gift-to-president-hollande.

2Ann Proctor, “Out of the Mould: Contemporary Sculptural Ceramics in Vietnam,” (PhD diss., Sydney University, 2006), 92.

3For an overview of ‘the law of unintended consequences’ see Rob Norton’s article “Unintended Consequences” at the Library of Economics and Liberty website: https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/UnintendedConsequences.html

4Nora Annesley Taylor, “The Artist and the State: The Politics of Painting and National Identity in Hanoi, Vietnam 1925–1995,” (PhD diss., Cornell University, 1997), 20

5A French colonial art prize established in 1910 by La Société Coloniale des Artistes Français to promote France’s colonies in East Asia. The prize was resumed following WWI and Tardieu became the second recipient in 1920. The award offered travel, accommodation, expenses and stipend for six months in French Indochina.

6Fonds Tardieu, Archives 125, 04, 07, n.p.

7Benezit Dictionary of Artists, (Oxford Online, 2011), n.p.

8The longest and one of the worst battles of WWI.

9Nancy Mowll Matthews, Paul Gaugin: An Erotic Life, (Boston: Yale University Press, 2001), 157-167.

10Jean Tardieu (1903–1995), in Corinne de Menonville, Vietnamese Painting: from Tradition to Modernity, (Paris: Les Editions d’Art et d’Histoire, 2003), 24.

11Fonds Victor Tardieu, 125.01.05, nomination de chevalier dans l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur.

12Fonds Victor Tardieu, 125.04.07, contrat pour la réalisation des décors de l’Université de Hanoï.

13Nguyễn Minh Huyền. “Reproducing a piece of history,” Việt Nam News, (May 14, 2006), n.p.

14Ibid., n.p.

15J.P. Daughton, “Behind the Imperial Curtain: International Humanitarian Efforts and the Critique of French Colonialism in the Interwar Years,” French Historical Studies 34, no. 3 (2012): 511.

16de Menonville, Vietnamese Painting, 24.

17William J. Duiker, Ho Chi Minh: a Life (New York: Hyperion, 2002), 50.

18Not all are officially identified. Some artists who are identified and also mentioned in this article, include, from left to right, (sitting) Joseph Inguimberty (6th); (1st line), Nguyễn Phan Chan (2nd), Lê Phổ (5th), Tô Ngọc Vân (6th), and Hồ Văn Lai (7th); (2nd line), Vũ Cao Đàm is on the far right in front of the pillar.

19Quang Việt, “The Fine Arts College of Indochina: A History,” in Painters of the Fine Arts College of Indochina, (Hanoi: NXB Mỹ Thuật, 1998), 139.

20Bertrand de Hartingh, “Historical Introduction,” in Vietnam Plastic and Visual Arts from 1925 to Our Time, (Brussells: Espace Méridien), 40..

21Huynh Tran Boi, “Vietnamese Aesthetics from 1925 Onwards,” (PhD diss., University of Sydney, 2005), 116.

22For a complete list of artists awarded the Prix de l’Indochine, see Appendix B.

23Nora Annesley Taylor, Painters in Hanoi: An Ethnography of Vietnamese Art, (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2004), 27.

24Huyhn Boi Tran, “Vietnamese Aesthetics,” 118.

25di San Marzano, “A Revolutionary Spirit: an introduction to Vietnamese Propaganda Art,” Dogma Collection (online): n.p.

26Ibid., n.p.

27Nguyễn Hoàng (1943- ), Vietnamese war artist.

28Taylor, Painters in Hanoi, 44.

29Hoang Dinh Tai, “Painter Nguyen Sang, Hoi painting and resistance,” Journal of the Fine Arts Department of Photography and Exhibition, (2015): n.p.

30Lisa Safford, “Art at the Crossroads: Lacquer Painting in French Vietnam,” Transcultural Studies, (2015): 126-170.

31Katharine Lockett, “Artists’ Materials and Techniques,” in Jennifer Harrison-Hall, Vietnam Behind the Lines: Images from the War, (The British Museum Press, 2002), 91.

32Elizabeth E. Guffey, Posters: A Global History, (Chicago: Reaktion Books, 2015), 8-13.

33For an examination of efforts to promote Indochina as a destination in the interwar years, see Erich de Wald, “The Development of Tourism in French Colonial Vietnam 1918–1940,” in Asian Tourism: Growth and Change, (London: Routledge, 2011).

34Phoebe Scott, “Art and the Press in the Colonial Period: Phong Hóa, Ngày Nay, and the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine,” in Essays on Modern and Contemporary Vietnamese Art, (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2008), 16.

35Other than the tourism poster, his EBAI enrolment details and the c. 1930 class photo the trail has gone cold on this enigmatic figure.

36Trinh Cung, “Vietnamese Art During the War,” in Essays on Modern and Contemporary Vietnamese Art, (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2008), 56.

37Taylor, Painters in Hanoi, 29.

38Ibid., 29.

39di San Marzano, “A Revolutionary Spirit”, n.p.

40Chu Quang Tru, Tranh co Viet Nam [Ancient Paintings of Vietnam], (Hanoi: Nha Xuat ban Van Hoa Thoang Tin, 1995), quoted in Taylor, Painters in Hanoi, 34.

41Nguyễn Phan, “The person who laid the first foundation for Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art,” Borrowing Time, (online): n.p.

42Shireen Naziree, From Art to Craft: Vietnamese Lacquer Painting, (Bangkok: Thavibu Gallery, 2013), 9.

43Nguyễn Quang Phòng, Painters of the Fine Arts College of Indochina, (Hanoi: NXB Mỹ thuật, 1998), 25.

| Home

| List Journal Issues | Table

of Contents |

| ©

2020 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois |

Content in World History Connected is intended for personal, noncommercial use only. You may not reproduce, publish, distribute, transmit, participate in the transfer or sale of, modify, create derivative works from, display, or in any way exploit the World History Connected database in whole or in part without the written permission of the copyright holder.

|

Terms and Conditions of Use

| |